Game Over

It seems rather obvious for anyone au courant of the latest developments in Cuba that the 60-year-old revolutionary experiment on the island has, for all practical purposes, already run its course.

Granted, the present government still holds all the trappings of authority left behind by its former masters and exerts total control over at least two essential levers of state power: the military and the state security services. It also oversees a failed shell of an economy.

What’s definitely true, though, is that after the patriarchal, big-brotherly despot who single-handedly presided a system devised in his own image entrusted his brother with some kind of regency for a country without heir, the regime started a slow period of irreversible transformations that definitely undermined the pillars of its 'success': a monopoly on information by the government and carefully enforced isolation.

Fast-forward some ten years and it is clear that in the aftermath of July 11th the government has exhausted most, if not all, of its political capital and has only managed to retain control through a combination of political repression and surreptitious encouragement of mass migration.

The underlying conditions that gave rise to the July 11th events, though, are still present and have, by all accounts, worsened: Cuba sits atop its most severe economic crisis in decades, with high inflation, chronic shortages of staple goods (and virtually any goods), never-ending waiting lines for basic necessities, nearly daily power black-outs, a collapsed healthcare system, an underfunded education system, crumbling infrastructure and an ineffective bureaucracy.

While it’s true that, except for a short-lived, mild respite during the 1980s and a brief period of relative bonanza between 2014 and 2019, all these ills have been a trademark feature of the regime during its 60-year-long existence, only the 1990s crisis and the one that started in the 2020s are comparable in intensity.

Why, then, does the current government still manage to retain power? Why didn’t July 11th become a national revolution? Why doesn’t pervasive social unrest lead to a renewed wave of demonstrations? Why is it that, for all its many grievances, the populace doesn’t seem to react the same way other impoverished, oppressed peoples have when suddenly hit by unbearable economic pressures? Why doesn’t a new wave of demonstrations spark again, when by all metrics, the situation worsens?

My thesis is that the answer lies in a well-known but often overlooked aspect of Cuba’s: its somehow quaint demographics.

Demography is destiny

I think the demographic profile of Cuba explains why the July 11th protests, albeit remarkable by Cuban standards, didn’t snowball into some kind of revolution, and I believe that the latest developments (which I will refer to) have only deepened the trends that will critically impair any attempt at successfully revolting again. In short, my thesis posits that beyond a certain median age threshold, populations are unlikely to violently revolt, and if they do, it's impossible (yes, impossible), for them to topple their governments.

Let’s take a closer look at it before I explain how and why the demographic profile of a country is relevant to the likelihood of a revolution taking place (and by revolution here I mean a massive, violent revolt that manages to topple the current regime, or nearly so).

Cuba is one of the most aged countries in Latin America, that’s common knowledge. As a matter of fact, it’s one of the most aged (and rapidly aging) countries in the world, but it is so in a rather unique way. After all, populations are aging worldwide, what is so special about it?

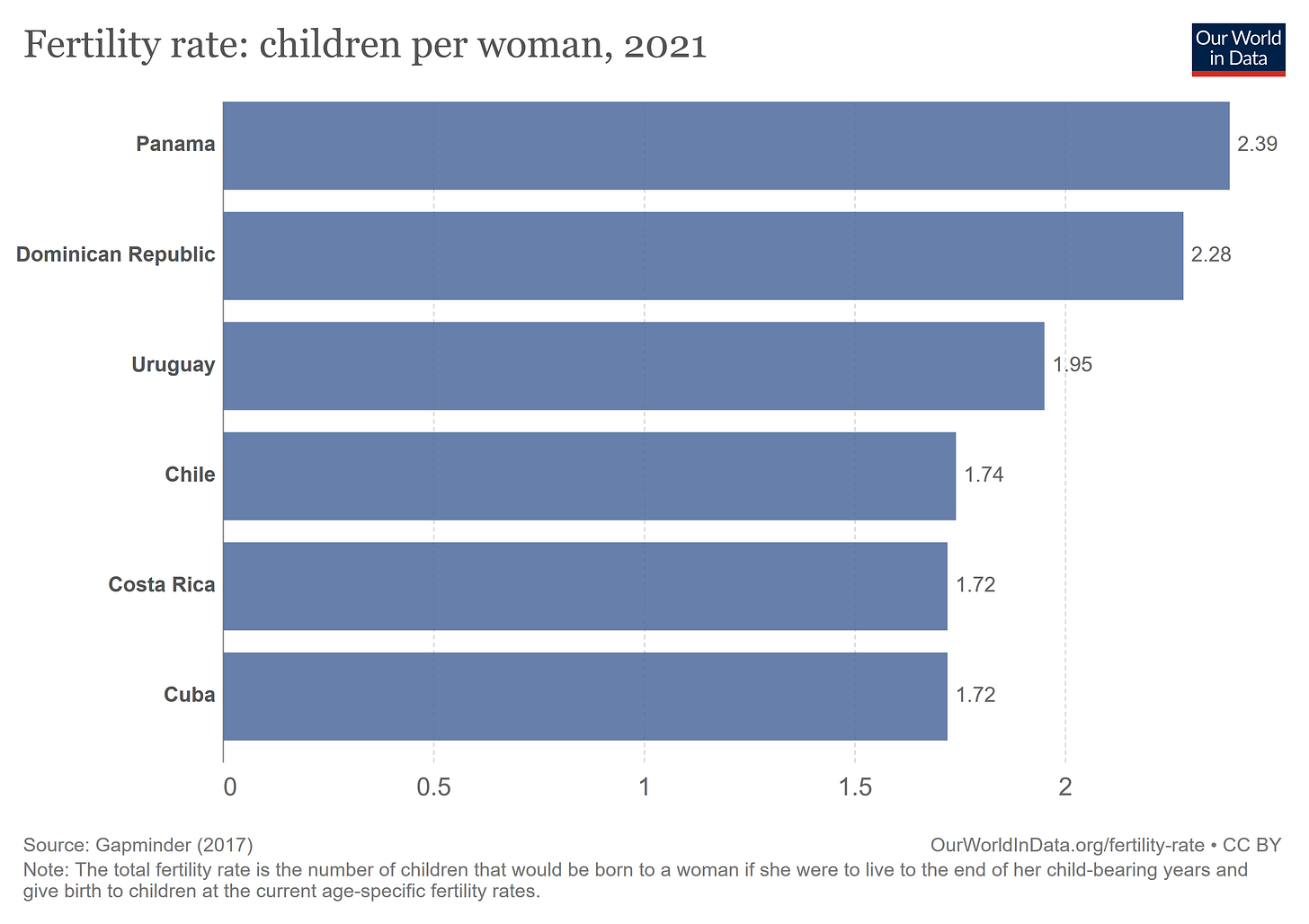

Cuba’s median age was a startling 41.2 in 2021 the year of the protests, well above the nearest most-aged Latin American country: Uruguay, which it is also significantly more aged than the region as a whole. Other Latin American countries have much younger populations. Cuba's fertility rate is not only way below replacement level, but more so than any other country in the area.

In fact, there’s only one Latin-American ‘country’ that’s ‘older’ than Cuba, but that I decided not to include in the first graphs because of several reasons, namely: while certainly being part of Latin America, it is not an independent nation, and its degree of economic development sets it apart from the rest of the area. I’m talking about Puerto Rico.

As you can see, excluding PR, which is certainly an outlier, Cuba is the most-aged country in the region. But that’s not its only distinctive feature. There are, after all, several countries with a comparable or higher median age.

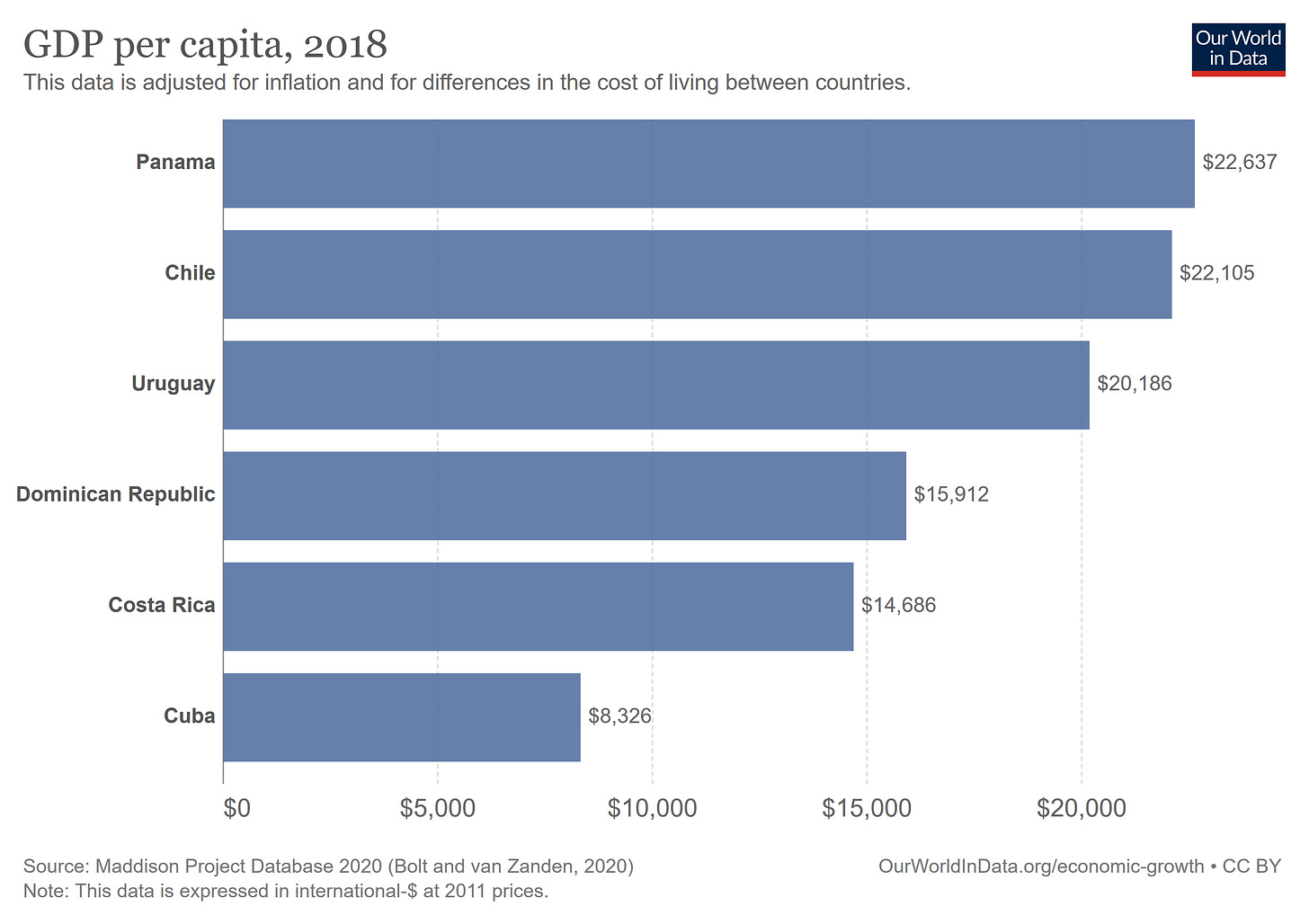

The issue at hand is that Cuba is both ‘older’ and comparatively poorer than its other Latin American counterparts, which is a phenomenon not typically observed, as higher per capita income is usually well correlated with lower fertility rates and a higher median age. Cuba is a notable outlier in this regard.

Since Our World in Data doesn’t have new information on Cuba’s GDP after 2018, I will use that year for comparison. Keep in mind, however, that Cuba is on an ongoing economic crisis and 2018’s statistics reflect a much better situation.

The gap is even more staggering if we take into account that economic data on Cuba have never been reliable anyway and the country in 2018 might have been even poorer than available statistics show.

If we include Puerto Rico, we see all the more clearly that per capita income is highly correlated with lower fertility and higher median age, and that Cuba is a freak outlier.

This does not mean that Cuba is the poorest country in Latin America, it certainly isn’t if its GDP per capita data are to be taken at face value. What makes Cuba special in this regard is that it is Latin America’s ‘oldest’ poor country. It is probably, in fact, the world’s ‘oldest’ poor country. A very rare combination of high median age and low GDP per capita.

In fact, Cuba’s demographic profile is so ‘first-world’ that can even be compared with that of some of the most developed countries in the world. For example, Norway’s fertility rate is higher than Cuba’s and the OECD countries median age is 39.9.

The mismatch between median age and wealth is becoming increasingly apparent. As previously noted, when per capita GDP is taken into account, Cuba is a rara avis: an unlikely blend of first-world demographics and third-world poverty.

The reasons for this are many and describing them in detail is not the main goal of my article but here are some: an early urbanization process that kicked off well before many of its Latin American counterparts (urbanization discourages the formation large families as child-rearing becomes more expensive in cities and dwelling space is usually scarcer), a relatively functional healthcare system (propped up by Soviet subsidies until 1991), free and accessible abortion services, a considerable portion of the female population that’s college-educated, adverse economic conditions and a number of exoduses that have plagued Cuba’s revolutionary history.

The Young shall inherit the Earth

But why is any of this relevant? What does median age have to do with revolutionary momentum?

The point is, of course, it does.

There are reasons to think that social unrest galvanizes under a certain set of conditions, one of which seems to be the existence of a relatively large cohort of people under at least thirty five years of age.

General dissatisfaction, disenfranchisement, political oppression, and widespread poverty are all important ingredients but violent upheavals, mass demonstrations and revolutions, especially if they are to succeed, depend ultimately on a large proportion of the population between ages 16 – 35 becoming enraged enough as to rock the system. If there are enough of them, the demonstrations will reach critical mass and whatever government they are revolting against might be unlikely to put down the protests. Nicolae Ceaușescu, for instance, was the only communist dictator that was violently toppled (and later executed) in what was largely an uprising by a huge cohort (Romania’s largest) of dissatisfied young people born under his rule as a result of his own draconian abortion ban of thirty years before.

In more democratic societies, where widespread grievances can be channeled through mostly peaceful means, the boomer generation (America’s and Europe’s largest) was for the most part the force behind cultural and social shifts that redefined Western societies.

In general, 'young' countries are more difficult to rule over, more prone to episodes of civil unrest and its populations less obedient. The typical images of passionate youngsters rising up against oppressive regimes or constraining social mores are not a visual rhetorical device after all.

A contemporary example of this are the so-called Arab Spring revolutions, a series of demonstrations and armed rebellions that swept across the Arab world, fueled by an alienated, neglected, massively unemployed young cohort that made up a huge portion of the total population.

Let’s compare:

It is worth noting that Cuba was already an aging nation in 2010, although less so than it is today. These Arab nations had a young cohort that was large enough as to effect change in their countries, or at least, create incommensurable chaos. Regardless of the aftermath of the Arab Spring, what’s true is that it wouldn’t have taken place without a gargantuan bulge of young people.

The last time Cuba had a similar demographic profile to that of, for example, Bahrain, was around 1995. And the country did saw, in 1994, the famous Maleconazo protests.

Whether the other pre-conditions for revolution were present in Cuba in 1994 is a different matter. 1994’s Cuba was certainly a much, much more isolated, less informed, less connected country and the regime still had a decent amount of political capital to burn and an extremely firm grip over the whole of society. La bête immonde was very much alive, and the repressive institutions at his disposal operated like clockwork, albeit in their trademark primitive fashion.

And what about 2010s Cuba, at the time of the Arab Spring? Let’s admit that Cuba at the time, even though it suffered from iterations of the same old evils consubstantial with the regime, was in much better shape that in the 1990s or 2020s. Leaving that important detail aside, was it still possible for a population nearing 40 to muster up enough strength as to, not rise up (that was possible in 2021), but topple the regime? Perhaps.

There’s a similar case.

In 2013 Cuba’s demographic profile was identical to Ukraine’s. In November of that year a series of protests broke out in Kiev and in February of the next year they managed to unseat their president and extirpate Ukraine of Russia’s area of influence (the rest of the story is well-known).

Had Cuba had its July 11th moment in 2013, the population might have, technically, been able to overthrow the government. Ukraine’s demographics show that it was still possible for a relatively aged society to effect a successful revolt. But around that time in Cuba it simply wasn’t THE moment. And it certainly wasn’t the case after 2016 and until 2018, when Obama’s thaw brought about a period of relative economic bonanza, and what was probably more important, a brief episode of intoxicating hope.

By the time the crisis that had slowly started in 2019 was aggravated by the Covid-19 pandemic and climaxed on July 11th 2021, Cuba’s youngest cohort had further shrunk and its median age was higher. The July 11th events might have been the country’s most fateful event in its recent history, but there’s reason to believe it was perhaps a futile rebellion, for the likelihood of the demonstrations reaching critical mass was already meager. Or perhaps not.

Perhaps it was Cuba’s last realistic attempt at toppling the regime (It did kill the capital R ‘Revolution’ for good, but that’s another story).

No Country for Young Men

What seems to be difficult to argue against, though, is the fact that after the ongoing exodus it is very unlikely that our demographics will allow for the kind of massive, dynamic upheaval that’s key for the government to collapse. At least, there's no example out there, past or present, of a revolution taking place in a place as aged as Cuba.

You could argue, nevertheless, that this is so because countries with aged populations are generally more prosperous, democratic, freer and politically stable, which, again, leaves Cuba as the only case which can prove or refute my theory and I believe the former to be more realistic.

This is a point on which I would like to be proven wrong, and as soon as possible. As I write, I hope for a re-ignition of protests in Cuba that may shatter my whole argument. But I’m not sure it will be the case.

The regimes of Egypt or Tunisia might have 2% of their population forced into exile and still be unable to quell violent dissent by an enraged youth, but Cuba doesn’t have the endless stream of young men and women the Arab world can boast of. Cuba is an emptying, aging country, and the oldest and emptiest it gets the farther away the likelihood of revolution lies.

Old men simply don’t do revolutions, and Cuba is no country for young men.

Interesting 🤔

Great observations